FOUCAULT, A. and NOBLET-DUCOUDRÉ, N. de (2005). Climate change at the origin of Eurasian mammoth extinction? 2nd International Congress "The World of Elephants". Hot Springs (SD), USA. 22-25 sept 2005. Short papers and abstracts, pp. 55-56.

Climate

change at the origin of Eurasian mammoth extinction ?

Alain

Foucault, Muséum

National d'Histoire Naturelle, Dépt. Histoire de la Terre, 43,

rue Buffon 75005

Paris, France, foucault@mnhn.fr

Nathalie

de Noblet-Ducoudré,

Laboratoire des Sciences du Climat et de l'Environnement,

Bat. 709, Orme des Merisiers, 91191 Gif-sur-Yvette, France, noblet@lsce.saclay.cea.fr.

About twelve thousand years ago, Mammuthus primigenius,

the wooly

mammoth, vanished from Earth. In Eurasia, some other big species ceased

to exist

at the same time, among them Coelodonta

antiquitatis, Bison priscus, Megaloceros

giganteus, Ursus spelaeus, Panthera

leo spelaea, Crocuta spelaea. Other big species changed their

habitats, for

instance Ovibos moschatus and Saiga

tatarica.

Several hypothesis have been proposed to

explain these extinctions. Three were recently discussed. Without an

order of

preference, the first one is that hunting has been fatal for big

species, the

second one is that a lethal virus killed the mammoths, the third one is

that

climate changes put an end to the big mammal fauna, not directly, but

through

substantial modifications of their environment. We evaluate here the

latest hypothesis

for Eurasia. Environmental changes that occurred after the Last Glacial

Maximum

(LGM) could indeed be a good reason to explain these extinctions.

Two complementary

approaches can be

used for this evaluation. The first one focuses on the reconstructed

paleo-environnement from discrete analysis of sediment records,

essentially the

palynologic content, and on geomorphic arguments. The drawback of this

approach

is the lack of regional distribution of such data, and therefore the

impossibility to reconstruct coherent changes over large geographical

regions.

The second one uses climate and biosphere models. Climate and biosphere

models

use variations in insolation as input data, and simulate all

atmospheric

variables, e.g. temperature, precipitation, as well as the distribution

of

vegetation that is in equilibrium with the simulated climate. The main

problem

scientists are faced with, using this approach, is the potential lack

of

important feedback in the modeling framework that has been built. This

is why

many studies are devoted to comparing model results to data at

different time

periods, to assert the realism of the model used.

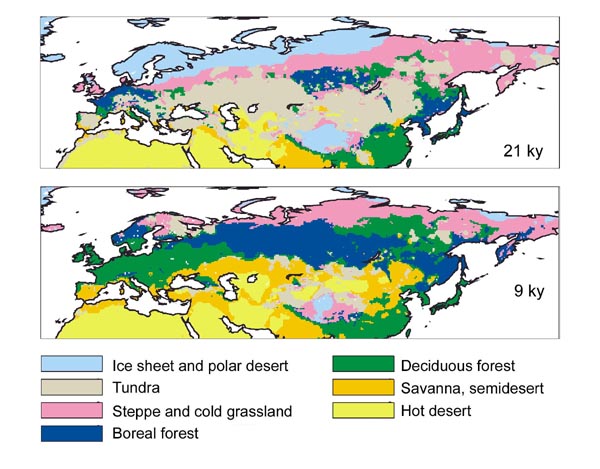

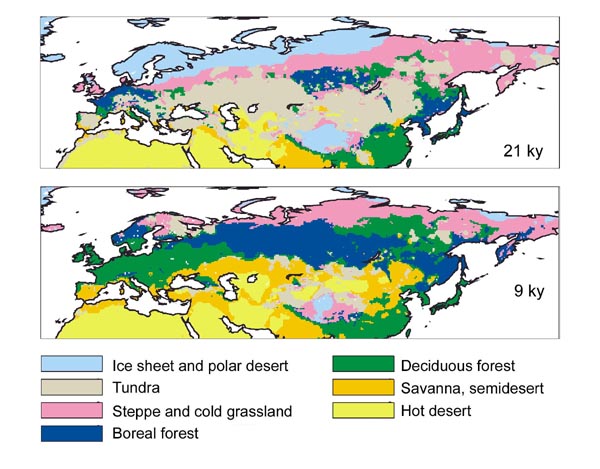

Maps issued from

modeling are far

more accurate in space and time than the ones issued from

sedimentological

records but some uncertainties remain about the repartition of biomes.

In our

case, if we compare the maps resulting from modeling presented here

(see figure)

with maps issued from palynologic and geomorphic data elaborated by

other

authors (1), we can see in some areas, as in western Europe, that,

during the

LGM, 21 000 years ago, the first ones showed forest whereas the

second

ones indicated steppes. These discrepancies could be attributed either

to

inaccuracies in mapping or to differences in the definitions of biomes.

Anyway,

both methods of mapping lead to the same general conclusions.

At the time of the LGM,

all the

non-glaciated parts of Eurasia were covered by tundra, tundra-steppe or

steppe.

This steppe is often called “mammoth steppe” (2) because of its

specific

composition that seems to have been particularly appreciated by this

big

mammal. Many authors have underlined that such a large extent of this

herbaceous association was the major reason for the great abundance and

variety

of herbivores that roamed this area at this time. Abundance and variety

of

carnivores ensue from the presence of their prey.

The climate change that

occurred

after the LGM was characterized by milder and wetter conditions less

favorable

for steppe growth but much more favorable for forest expansion.

Consequently,

forests that had taken refuge in few areas during the LGM, gradually

spread out

at the expense of the steppe. All maps of vegetation distribution show

that,

9000 years ago, there were very few remaining areas covered with steppe

vegetation in Northern Eurasia. The Northern part was occupied by a

tundra,

bordered to the South by a large belt of forests, deciduous forest to

the West,

and boreal forest to the East.

Without the steppe, or

at least

without larges areas of steppe in the Northern part of Eurasia, the

former association

of herbivores could not continue to exist and we are allowed to assume

that

these environmental changes have been sufficient to explain the

extinction of

several big species and the emigration of others. However, it is

difficult, in

the limited precision of our models, to certify that areas of steppe

did not

remain here and there, and could have been refuges for big herbivores

as it was

the case for St Paul (3) and Wrangel (4) Islands where mammoths

survived until

8000 and 3700 years BP respectively. For this reason, we cannot reject

the

hypothesis that hunting was the ultimate factor that put an end to

mammoth’s

life. But in this case, the same explanation has to be true for the

other

species that disappeared with them.

In conclusion, climate and environmental changes that occurred after the LGM seem a sufficient circumstance to explain the extinction of mammoths and associated faunas. Modeling of biome distribution must be improved to test the hypothesis that little populations of these mammals could have remained in refuges and eventually could have been killed by hunting.

(1) e.g.Petit-Maire, N. and

Bouysse, P. (coord.), 1999. Maps of the

World Environment during the last two Climatic Extremes. Commission

for the Geological Map of the World and ANDRA.

(2)

Guthrie, R. Dale, 1990. Frozen Fauna of the Mammoth Steppe: The Story

of Blue

Babe. The

University of Chicago Press.

(3) Guthrie, R. Dale, 2004. Nature 429:746-747.

(4) Vartanyan, S. L.,

Arslanov, Kh. A., Tertychnaya, T. V.,

Chernov, S. B., 1995. Radiocarbon 37

(1):1-6.

Figure.

Biome distribution 21 ky and 9 ky ago.